HMS Gosling and HMS Ariel

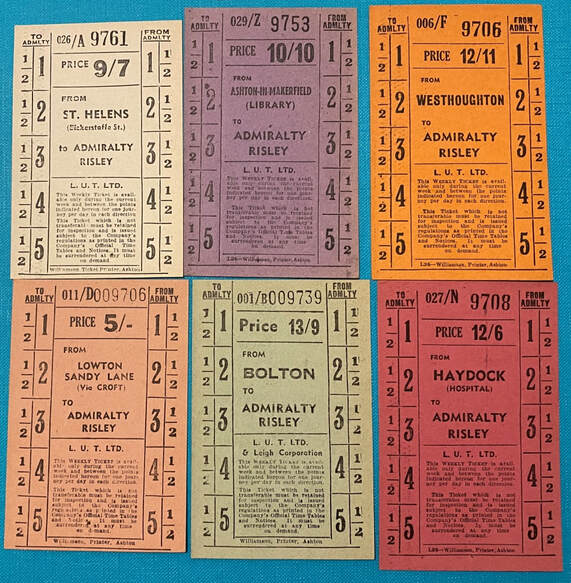

Opened in July 1942, Royal Naval Air Training Establishment HMS Gosling was to be the Fleet Air Arm training depot for Air Fitters, Air Mechanics and Radio Mechanics. It also trained Royal Marines of the Royal Naval Air Station Defence Force.

HMS Gosling was such a large establishment it comprised of 5 separate, dispersed, sites; the Headquarters and administrative centre was at Camp 1 New Lane, Croft. The other four sites were training camps - Camp 2 at Risley, Camp 3 Lady Lane, Croft, Camp 4 at Lowton, and Camp 5 at Glazebrook.

The establishment was collectively named as Royal Naval Aircraft Training Establishment Risley.

Shortly after Gosling opened a further site was acquired at Culcheth for accommodating Naval and WRNS radio mechanics for the Fleet Air Arm for the final stage of technical training, this site was to be commissioned as HMS Ariel on October 8th 1942 with its accounts being held by Gosling.

After initial assessment at recruiting depots, new entrants arrived at Camp 1 for joining routine before being allocated to Camp 4 for 12 weeks basic training - This included a week at RAF Sealand, Flintshire, where trainees attended the rifle and grenade live firing range.

Depending on the results of aptitude testing on completion of this initial training they were sent to other Gosling camps, or to other training establishments, for trade training. Air Radio Mechanics went to HMS Ariel.

After WW2, on the 21st October 1947, the Royal Navy left and the site was decommissioned.

HMS Gosling was such a large establishment it comprised of 5 separate, dispersed, sites; the Headquarters and administrative centre was at Camp 1 New Lane, Croft. The other four sites were training camps - Camp 2 at Risley, Camp 3 Lady Lane, Croft, Camp 4 at Lowton, and Camp 5 at Glazebrook.

The establishment was collectively named as Royal Naval Aircraft Training Establishment Risley.

Shortly after Gosling opened a further site was acquired at Culcheth for accommodating Naval and WRNS radio mechanics for the Fleet Air Arm for the final stage of technical training, this site was to be commissioned as HMS Ariel on October 8th 1942 with its accounts being held by Gosling.

After initial assessment at recruiting depots, new entrants arrived at Camp 1 for joining routine before being allocated to Camp 4 for 12 weeks basic training - This included a week at RAF Sealand, Flintshire, where trainees attended the rifle and grenade live firing range.

Depending on the results of aptitude testing on completion of this initial training they were sent to other Gosling camps, or to other training establishments, for trade training. Air Radio Mechanics went to HMS Ariel.

After WW2, on the 21st October 1947, the Royal Navy left and the site was decommissioned.

RAF Croft

During the mid-1950s the Croft site was renamed RAF Croft and became tenanted by the United States Air Force as a transient base for American personnel and their dependents from nearby RAF Burtonwood.

On the 1st February 1956, the 7500th airbase squadron under the umbrella of MATS (Military Air Transport Services) arrived at Croft for the handling of all American personnel arriving and departing the United Kingdom by aircraft from and to the United States.

Croft handled over 60,000 passengers a year, the passengers being transported between RAF Burtonwood and RAF Croft by bus. RAF Burtonwood operated a fleet of 35 single-decker buses with a capacity of 29 passengers each.

Croft operated 7 days a week 24 hours a day processing all personnel arriving and departing.

A large theatre was located on the station and regularly showed 16mm films.

Almost anybody who had some military connection and flew MATS came through. Air Force, Navy, Coast Guard, exchange people, civilians working on missile programs and of course dependent wives and children.

In fact, twice as many people were shipped out as were shipped in.

A Staff Sergeant recalls:

“I don’t think that many single military types made it out of England without a wife if they served a full tour.”

“When flying operations closed at Burtonwood and passengers were processed through Mildenhall, the system changed and personnel from Croft were scattered far and wide.”

“Phasing down the base took some time as all the property had to be turned in to supply Burtonwood and the barracks had to be left in pristine condition. We must have burned at least ten tons of trash.

At the end there were only three of us left. We moved into the guardroom at the front gate until it was time to turn over the base to the RAF.

All of our work cleaning up the base was for nothing. When I visited the base in 1991/92, the hall was full of chickens and all the barracks were gone. The only trace of the barracks were the floor tiles on the ground. Other buildings held farm machinery and the base probably will be bulldozed out of existence when the developers need the land for housing.”

The site is indeed now a housing estate.

Source - Historic Aviation Military

On the 1st February 1956, the 7500th airbase squadron under the umbrella of MATS (Military Air Transport Services) arrived at Croft for the handling of all American personnel arriving and departing the United Kingdom by aircraft from and to the United States.

Croft handled over 60,000 passengers a year, the passengers being transported between RAF Burtonwood and RAF Croft by bus. RAF Burtonwood operated a fleet of 35 single-decker buses with a capacity of 29 passengers each.

Croft operated 7 days a week 24 hours a day processing all personnel arriving and departing.

A large theatre was located on the station and regularly showed 16mm films.

Almost anybody who had some military connection and flew MATS came through. Air Force, Navy, Coast Guard, exchange people, civilians working on missile programs and of course dependent wives and children.

In fact, twice as many people were shipped out as were shipped in.

A Staff Sergeant recalls:

“I don’t think that many single military types made it out of England without a wife if they served a full tour.”

“When flying operations closed at Burtonwood and passengers were processed through Mildenhall, the system changed and personnel from Croft were scattered far and wide.”

“Phasing down the base took some time as all the property had to be turned in to supply Burtonwood and the barracks had to be left in pristine condition. We must have burned at least ten tons of trash.

At the end there were only three of us left. We moved into the guardroom at the front gate until it was time to turn over the base to the RAF.

All of our work cleaning up the base was for nothing. When I visited the base in 1991/92, the hall was full of chickens and all the barracks were gone. The only trace of the barracks were the floor tiles on the ground. Other buildings held farm machinery and the base probably will be bulldozed out of existence when the developers need the land for housing.”

The site is indeed now a housing estate.

Source - Historic Aviation Military

RAF Padgate

Padgate had a small RAF base which provided basic training for air force recruits. It opened in April 1939.

The site of the RAF base is now a housing estate, bordering Cinnamon Brow.

Vulcan Close, Valiant Close, Anson Close, Harrier Road, Viscount Road, Blenheim Close, Lancaster Close and Wellington Close are just some of the street names in the Blackbrook area of the town which are named after airplanes used in the war.

The university campus in nearby Fearnhead, affiliated to the University of Chester, was used as a camp for Canadian servicemen (called Canada Hall) during the Second World War, before becoming a teacher training college in 1946. This was used to house some of the servicemen stationed at Burtonwood.

Around 4,000 personnel were stationed at RAF Padgate during its lifetime.

The site of the RAF base is now a housing estate, bordering Cinnamon Brow.

Vulcan Close, Valiant Close, Anson Close, Harrier Road, Viscount Road, Blenheim Close, Lancaster Close and Wellington Close are just some of the street names in the Blackbrook area of the town which are named after airplanes used in the war.

The university campus in nearby Fearnhead, affiliated to the University of Chester, was used as a camp for Canadian servicemen (called Canada Hall) during the Second World War, before becoming a teacher training college in 1946. This was used to house some of the servicemen stationed at Burtonwood.

Around 4,000 personnel were stationed at RAF Padgate during its lifetime.

ROF Risley

ROF Risley was a Royal Ordnance Factory that specialised in filling and priming shells and bombs during

World War Two.

In August 1939 Britain faced a desperate race against time to re-arm itself, ready for the coming war against Hitler’s Germany. The order went out for Royal Ordnance Factories to be built, away from the threat of German bombers in London, and preferably in areas of high unemployment.

Risley ROF was one of several Filling Factories commissioned when war seemed inevitable. In such factories metal components were filled with explosive to make complete rounds of ammunition and bombs.

Construction began in August 1939. It took 18 months to complete, but bombs were produced from September 1940.

Risley was chosen because it was flat and often covered with mist. It turned out to be a good decision as it was never bombed.

More than 22,000 people were employed by 1942. Nearly all the workers were women from Leigh, Warrington, Liverpool and Manchester. Some male workers were ex-miners from Leigh. The workforce was brought in by bus from nearby towns or purpose-built hostels at Culcheth and Padgate.

World War Two.

In August 1939 Britain faced a desperate race against time to re-arm itself, ready for the coming war against Hitler’s Germany. The order went out for Royal Ordnance Factories to be built, away from the threat of German bombers in London, and preferably in areas of high unemployment.

Risley ROF was one of several Filling Factories commissioned when war seemed inevitable. In such factories metal components were filled with explosive to make complete rounds of ammunition and bombs.

Construction began in August 1939. It took 18 months to complete, but bombs were produced from September 1940.

Risley was chosen because it was flat and often covered with mist. It turned out to be a good decision as it was never bombed.

More than 22,000 people were employed by 1942. Nearly all the workers were women from Leigh, Warrington, Liverpool and Manchester. Some male workers were ex-miners from Leigh. The workforce was brought in by bus from nearby towns or purpose-built hostels at Culcheth and Padgate.

More than half a million bombs and more than a million mines were assembled at the factory, including the 22,000lb bomb or ‘Grand Slam' which sank the German battleship 'Tirpitz' in November 1944.

The factory was divided into ‘clean’ and ‘dirty’ areas. In ‘cleanways’, where detonators were filled, workers wore special clothing with no zips or metal components.

Jewellery was forbidden except for wedding rings, which were covered up with sticking plasters and the ‘clean’ areas were constantly vacuumed so that no gunpowder particles could accumulate.

Filling shells was fiddly and dangerous. The women wore special safety gloves, and their faces were protected by a reinforced glass screen. Some workers, tired of wearing the heavy gloves, took them off - but the heat from their fingers could set off the explosive. Many girls lost fingers as a result.

The explosive powder gave many workers a condition called the 'coup'.

A local woman who was an Inspector in 1941 said “It was vital for every shell to be perfect. Eventually we all became yellow — hair, face, hands, it wouldn’t wash off. My hair went blonde — I liked it and it stayed that way. We also got big boils on our skin from the powder."

Some of the shells were very heavy to handle: "I was examining 25lb shells and dropped one on my foot," she said. "I was limping, but I still went to work."

As security so important, workers in one part of the building were not allowed into other areas.

The factory had its own internal railway network to carry goods and materials. To reduce the risk of sparks from the wheels setting off an explosion, the tracks were made of phosphor bronze.

One woman who drove lorries laden with explosives said "One night, in thick fog, with a hill load, the lorry got it's back wheels stuck on the railway lines. Luckily some Americans came by in a Jeep and towed the lorry off the track."

Nearby Risley Moss was used to test bombs and ammunition. Dorothy Barker said: "At night I would take the smokescreen cylinders up to Risley Halt (now Birchwood station.) The workmen would test them to see how dense the smoke was".

Workers could relax in the canteen, where cigarettes were sold just one at a time so that no-one could be tempted to take one outside (any worker found with a match or cigarette in a Danger Area faced instant dismissal).

The site was taken over by the Admiralty, which in 1956 sold part of the site to the United Kingdom Atomic Energy Authority for its Northern Headquarters. The Admiralty left in 1961, and the site was left to rot — it was one of the largest derelict land areas in Britain.

In 1968 it was acquired by Warrington New Town Development Corporation. Demolition began in the 1970s - but the Factory’s 20 explosives bunkers or ‘magazines’ caused a major headache. Strongly built, with concrete sides, they were grassed over on top, and sheep grazed there during the war to help disguise them from the air.

They were so solidly built, in fact, that it took twice as long to demolish the factory as it had taken to build it in the first place.

Four of the bunkers were close to the Universities’ Nuclear Reactor, so they could not be blown up. They were kept as landscape features and can still be seen today at Birchwood Forest Park. The foundations of the other bunkers were covered with soil and lie beneath the park’s sports pitch and playing fields.

Risley Moss was developed into a nature reserve, and is now a Site of Special Scientific Interest, the home to many different birds, animals, and rare plants including 11 species of dragonfly alone.

Only the grass-covered bunkers remain as silent monuments to the unsung heroes and heroines

who helped to win the war.

Source - WW2 People's War is an online archive of wartime memories contributed by members of the public and

gathered by the BBC.

The archive can be found at bbc.co.uk/ww2peopleswar

The factory was divided into ‘clean’ and ‘dirty’ areas. In ‘cleanways’, where detonators were filled, workers wore special clothing with no zips or metal components.

Jewellery was forbidden except for wedding rings, which were covered up with sticking plasters and the ‘clean’ areas were constantly vacuumed so that no gunpowder particles could accumulate.

Filling shells was fiddly and dangerous. The women wore special safety gloves, and their faces were protected by a reinforced glass screen. Some workers, tired of wearing the heavy gloves, took them off - but the heat from their fingers could set off the explosive. Many girls lost fingers as a result.

The explosive powder gave many workers a condition called the 'coup'.

A local woman who was an Inspector in 1941 said “It was vital for every shell to be perfect. Eventually we all became yellow — hair, face, hands, it wouldn’t wash off. My hair went blonde — I liked it and it stayed that way. We also got big boils on our skin from the powder."

Some of the shells were very heavy to handle: "I was examining 25lb shells and dropped one on my foot," she said. "I was limping, but I still went to work."

As security so important, workers in one part of the building were not allowed into other areas.

The factory had its own internal railway network to carry goods and materials. To reduce the risk of sparks from the wheels setting off an explosion, the tracks were made of phosphor bronze.

One woman who drove lorries laden with explosives said "One night, in thick fog, with a hill load, the lorry got it's back wheels stuck on the railway lines. Luckily some Americans came by in a Jeep and towed the lorry off the track."

Nearby Risley Moss was used to test bombs and ammunition. Dorothy Barker said: "At night I would take the smokescreen cylinders up to Risley Halt (now Birchwood station.) The workmen would test them to see how dense the smoke was".

Workers could relax in the canteen, where cigarettes were sold just one at a time so that no-one could be tempted to take one outside (any worker found with a match or cigarette in a Danger Area faced instant dismissal).

The site was taken over by the Admiralty, which in 1956 sold part of the site to the United Kingdom Atomic Energy Authority for its Northern Headquarters. The Admiralty left in 1961, and the site was left to rot — it was one of the largest derelict land areas in Britain.

In 1968 it was acquired by Warrington New Town Development Corporation. Demolition began in the 1970s - but the Factory’s 20 explosives bunkers or ‘magazines’ caused a major headache. Strongly built, with concrete sides, they were grassed over on top, and sheep grazed there during the war to help disguise them from the air.

They were so solidly built, in fact, that it took twice as long to demolish the factory as it had taken to build it in the first place.

Four of the bunkers were close to the Universities’ Nuclear Reactor, so they could not be blown up. They were kept as landscape features and can still be seen today at Birchwood Forest Park. The foundations of the other bunkers were covered with soil and lie beneath the park’s sports pitch and playing fields.

Risley Moss was developed into a nature reserve, and is now a Site of Special Scientific Interest, the home to many different birds, animals, and rare plants including 11 species of dragonfly alone.

Only the grass-covered bunkers remain as silent monuments to the unsung heroes and heroines

who helped to win the war.

Source - WW2 People's War is an online archive of wartime memories contributed by members of the public and

gathered by the BBC.

The archive can be found at bbc.co.uk/ww2peopleswar